Critical Thinking on Gene Technology Regulation

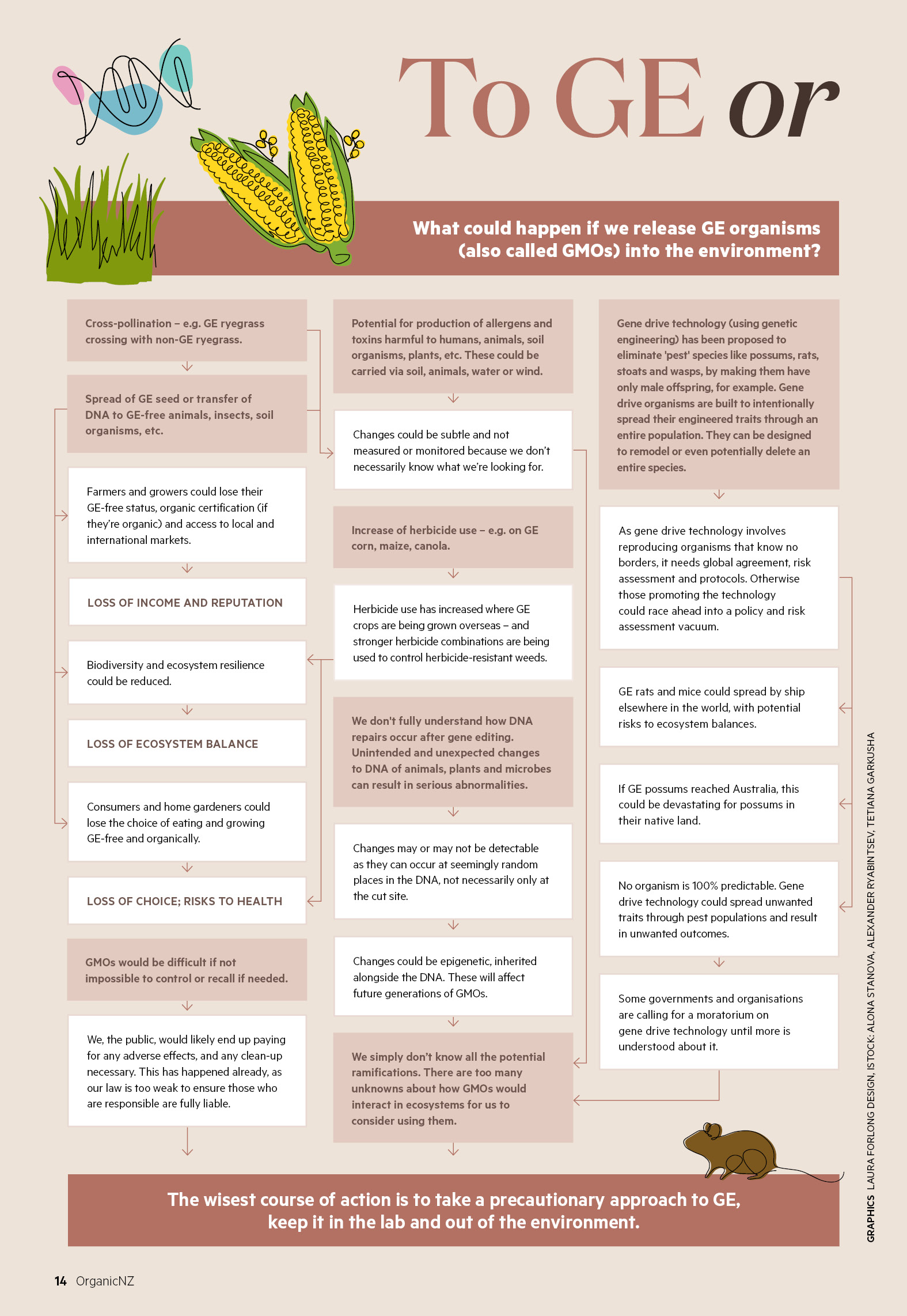

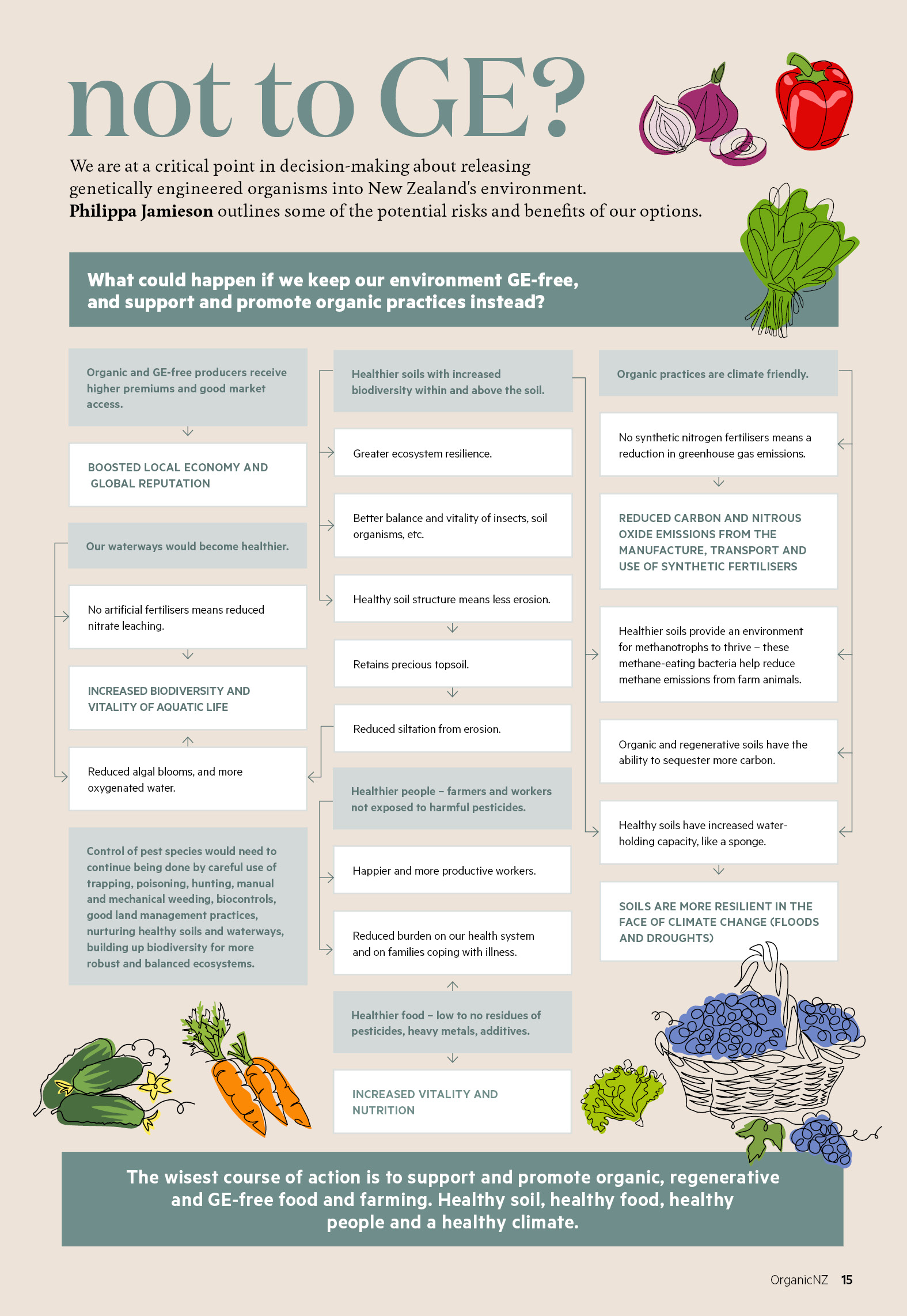

Layers of manipulation and obfuscation are being used to package deregulation of gene technologies as a net positive. Bonnie Flaws outlines how, and why one of New Zealand’s leading biological science professors considers regulation the best tool we have to prevent risk.

We hope you enjoy this free article from OrganicNZ. Join us to access more, exclusive members-only content.

New Zealand is once again having a public debate about the regulation of GMOs, with plans to overhaul the existing system now laid out by the National-led coalition government. For decades, genetically modified organisms, and latterly gene edited organisms, have been regulated under the Hazardous Substances and New Organisms Act 1996 (HSNO). The passing of this Act led to the establishment of the Environmental Protection Authority (previously the Environmental Risk Management Authority).

This is the body responsible for overseeing the importation, development, field trials and releases of GMOs, allowing scientists to experiment with GM techniques in the lab and in contained field trials. Responsibility for GMOs in food is covered by a joint New Zealand and Australian body, Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ) and regulated through the Food Standards Australia New Zealand Act.

In Northland and Hawke’s Bay, local government restricts agricultural GMOs under the Resource Management Act. In 2014, the courts ruled that newer synthetic biology and gene editing techniques are GMOs for the purposes of regulation under HSNO, making New Zealand the first country to do so globally. Professor Jack Heinemann from the School of Biological Sciences at the University of Canterbury was the expert witness in that hearing, pointing out that it is a technology’s scalability that primarily makes it risky.

The momentum behind the latest push for loosening the rules on GMOs comes from the usual proponents – corporate interests in medicine, horticulture, agriculture and food production, as well as industrial manufacturing. They argue, on the whole, that allowing the alteration of gene function and expression will lead to new vaccines and gene therapies for disease and other useful medical substances, pest-resistant plants, prevent world hunger, and reduce greenhouse gases.

Now, the coalition government is moving ahead with plans to change the way these laws will govern gene technologies by removing restrictions and creating a dedicated regulator within the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE). The new regulator would streamline approvals for trials in line with countries like the US, Australia, and the UK.

The arguments that are being put forward in favour of this, as outlined in National’s Harnessing Biotech policy document, include combatting climate change, advancing health care, safeguarding the natural environment, and lifting agricultural productivity.

Importantly, it would also deregulate the use of non- GE/GM biotech, or perhaps more accurately technologies the regulator considers ‘out of scope’ for regulation, or which are not defined as GMOs, but which arguably should be.

New techniques used to advance deregulation

In a recent Soil & Health NZ webinar delving into the world of genetic engineering, Heinemann pointed out that every time a new technique is developed in this arena, it is used to undermine confidence in regulation.

Gene editing is the most obvious example, and with that battle lost in the courts we are now informed that null segregants – the offspring of genetically modified organisms, which do not contain any genetic modifications themselves – are considered ‘out of scope’. In February, the EPA clarified that as far as regulation is concerned, null sergregants will not be considered genetically modified organisms.

Heinemann says we’ve seen this tactic used repeatedly since the 1980s.

“There’s the same type of language being used now as has been used for the last thirty or forty years, on almost a repeating tape, to try and undermine people’s confidence in what they are trying to achieve [with strong regulation].”

Just because new techniques are developed doesn’t mean our laws are automatically out of date. For example, take road safety rules. We wouldn’t reconsider speed limits just because electric cars are now common. The nature of the specific risk doesn’t change.

Labelling and the right to choose

What the public hopes to achieve with regulation is worth stating clearly. It is the safe use of gene technology biologically speaking, but also in the social sense: maintaining our ability and right to choose.

Heinemann believes the biggest lever in this discussion is labelling. Despite there being very little evidence that these technologies do a good job of delivering useful products to society, vested interests continue to attempt to get rid of labelling provisions, he says.

But because removing labelling has been unsuccessful in most countries, lobbyists are now focused on deregulation for certain uses. Once deregulated, such products would no longer be subject to labelling provisions.

Contamination and detection

Heinemann points out that in an unregulated environment, if an ‘out of scope’ organism gets into someone else’s GMO-free product line, the developer would have no liability. “If it doesn’t have to be labelled and it’s not legally a GMO and they don’t have to call it a GMO, then their argument to you would be, there is no GMO contaminating your product line. Which is why defining them ‘out of scope’ undermines labelling laws and market certifications.”

Detection after the fact can also become an issue, he says. Heinemann gives the example of a space person landing on Earth. They would have no way of knowing if the flora and fauna they find is indigenous to Earth – unless people tell them.

Likewise, unless the gene technology developer gives regulators the tools and the information to identify a genetically-modified plant genome, until recently they wouldn’t be able to do so. That’s why in Europe there was a requirement that in exchange for approval, developers had to provide a technique for detection.

Heinemann notes that if deregulation were to go ahead there would be no effective way whatsoever to prevent contamination of non-GMO and organic crops, asserting that regulation remains the best way to prevent contamination. “[Regulations] are not perfect, but they are better than not having them at all. Using regulation is the most effective means we have so far invented to contain the potential for our technologies to cause harm.”

Nature vs. technology

No technology is benign, and we can’t afford to be complacent about it, no matter how sophisticated industry arguments become. Whether true or not, a technology being similar to nature is not an argument for deregulation.

“When a uranium atom decays in the environment, it is the same as a uranium atom decaying in an atomic bomb. That’s not the point. Whether the biochemical reaction of a change in a DNA sequence can be the same in a laboratory, or outside of a laboratory, is not the point. The difference is the use of a technology, which makes more efficient and scalable the production of goods,” Heinemann says.

In other words, it’s the scalability of a technology that makes it risky.

Accountability and risk assessment

Further, if deregulation goes ahead, detection techniques will be used only to protect intellectual property, not to protect consumers from unidentified genetically-modified products. Heinemann notes that developers have to be able to show a court that a piece of intellectual property is theirs, and they do this using a detection technique.

Deregulation won’t change our ability to detect them, but they will provide a licence to keep those techniques secret. Therefore, these techniques won’t improve biosafety, because they would not be able to be used for routine monitoring, or to underwrite labelling laws, he says.

From Heinemann’s perspective the important thing to do is not define something ‘out of scope’. Regulators could still use different standards for assessing various gene technologies, which is how the system currently operates under HSNO.

The most obvious example being whether a scientist is using gene technologies in a lab versus in the open environment. “You can have a different standard in a lab, because of the checks and balances built into that process. But if you deregulate a different type of tool, it can be done in your garage.”

By defining a genetic technology as ‘out of scope’, the regulator removes accountability regarding risk or safety and the public’s right to know and choose.

Bonnie Flaws is a freelance journalist who lives in Napier. She has a personal interest in organics and agroecological farming.