Silt to soil: Rejuvenating silt organically

The silts from recent floods are devoid of the all-important pore spaces, organic matter and microbes that make up a living soil. Charles Merfield gives practical recommendations on how to use organic processes to re-establish these and revitalise mineral-rich silt.

We hope you enjoy this free article from OrganicNZ. Join us to access more, exclusive members-only content.

An ideal soil is 45 per cent mineral, 5 per cent organic matter and 50 per cent pore spaces occupied equally by air and water.

What is silt?

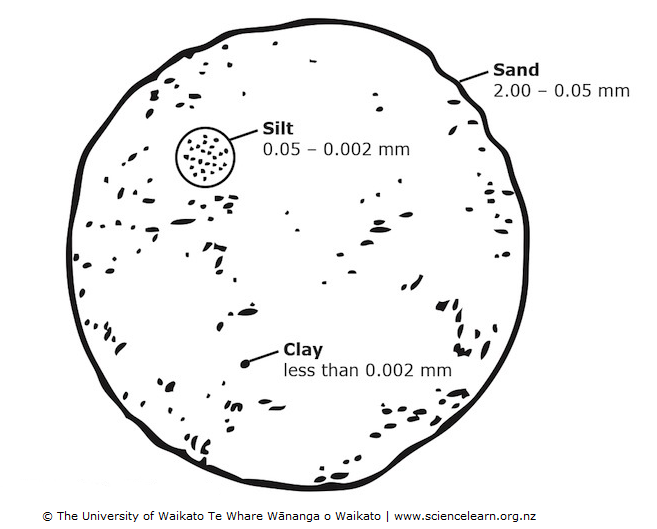

Silt, sand, and clay are terms for specific sizes of the rock particles that make up soil – see figure 1 above.

Silt is left on flatter areas after flooding because the water currents are too slow to carry sand, and clay is so small and light it stays in suspension. Silt is also used as a general term for finer materials left behind by floods.

The east coast of the North Island has been particularly badly affected by flooding from Cyclone Gabrielle because many of its rocks are siltstones and mudstones. There are predominantly made of silt and clay particles, and they are highly erodible, so large amounts were carried by the floodwaters.

Silts left behind by flooding (and also deposited by wind), is how many of Aotearoa New Zealand’s extremely fertile soils began, then vegetation built up the organic matter, biology, and structure to form soil. While flood silt is not soil, it can be transformed into soil, often highly fertile soil. This can take a few, or tens of years, depending on approach.

Contamination

The first thing to determine is if flood silt is contaminated with harmful materials. Most biological materials such as sewage will naturally decompose over time so in the long-term they will not be damaging.

If it is suspected synthetic chemicals have been washed down, it is a much more complex problem and the effect will depend on the exact chemicals and their amounts. This issue is too technical to cover here, you need expert advice. Start by contacting your council and if you are organically certified, talk with your certifier.

Integration

How best to deal with the silt depends on how deep it is.

If it is less than 20 cm deep it can be dug in or cultivated into the soil below. This should bring the soil back to a form of normality quite quickly. Experience on pasture has shown that mixing the silt with original soil improved recovery, both short and longer term. Cultivation also destroys the interface between original soil and silt which can be a barrier to air, water and roots.

Between 20 cm and 60 cm deep it can be cultivated in, but, doing this manually in a garden will be very challenging, and even commercially, specialised equipment, e.g., a spading machine is likely to be required. Also, the amount of silt will be greater than the original topsoil meaning it will take longer to get back to full health.

Beyond 60 cm the silt will have to be removed if it is causing other problems, e.g., has buried infrastructure or is killing perennial plants or trees.

Incorporation

If the silt is not removed, then the best action is to get plants growing as quickly as possible to start the process of turning the silt into soil.

Some perennial plants, such as kiwifruit and citrus have low tolerance of waterlogging and anaerobic soils. For these species clearing the silt about 30 to 50 cm from around the trunks within 48 hours may be the difference between the plants living or dying. Sadly this will have been impossible or impractical in many situations.

Biological materials such as compost and manure and incorporated into the silt that can really kick start the soil-forming processes. Five per cent soil organic matter can equate to 500 to 1000 tonnes of organic matter per ha, so, in this situation putting on hundreds of tonnes of compost can be justified, if at all feasible. This will also boost the populations of soil microbes in the silt, to help its transformation into soil.

Regeneration

While silt will have very few soil microbes and other biology in it compared with healthy soil, it is far from sterile. Soil microbes are blowing around on the wind all the time. To get soil biology amongst the silt requires living plants.

Living plants, particularly the exudates from their roots (see the article ‘Humus is dead – long live MAOM’ in print version of OrganicNZ Nov/Dec 22), are what turns silt to soil. Any plants are good and the more diversity of species the better. However, there are a number issues to take into account when deciding which species to use.

- The seed needs to be readily available and not expensive. This typically means pasture and arable species, i.e., cover crops.

- Species need to be suitable for your climate and also the time of year, i.e., don’t plant frost sensitive species in autumn / winter in cooler areas.

- The plants need to grow quickly. To hold the silt together when it rains and stop it blowing around as dust in the dry. That also means pasture, and especially annual arable species / cover crops are best.

- You need all three of the herbaceous (i.e., pasture and arable) functional plant groups: grasses, legumes and forbs (herbs).

- Grasses have fine fibrous root systems that are very good at holding onto the silt and keeping it in place. Annual arable species such as ryecorn, triticale, and maize have deep rooting systems which will hold onto more soil and grow into the original soil to tap into its nutrients.

- Legumes can fix nitrogen which will be in short supply. However, legumes need the right symbiotic bacteria to do the fixing, which may not be present in enough numbers in the silt. It is probable that white clover, being so ubiquitous across New Zealand, may be OK. Other species are likely to need inoculum applied with the seed. Inoculums are species specific. Talk with your seed supplier.

- Forbs are everything that is not a grass or a legume. Put in what ever you can, especially some deeper rooting species such as chicory (perennial) and sunflowers (annual) as these can ‘punch’ through the silt into the original soil and help transport soil microbes up into the silt. They will also help get oxygen down into the original soil as their roots die and create air channels.

- Annuals are generally much faster growing than perennials which is what is needed for quick establishment to protect the silt from wind and rain, but, they only grow for a few months. Try mixing some perennials’ seed in with the annuals’ seed so once the annuals are finished the perennials can come through. This is a form of undersowing described in the article ‘The root of the matter: Intercropping and living mulches’ in the print version of OrganicNZ Jan/Feb 23.

- Avoid species that don’t tolerate wet conditions, lucerne is the obvious example, as they wont like the anaerobic conditions in the silt. Ask your seed supplier.

- The exact species are not critical – the really critical thing is to get the silt sown with something rather than nothing, and sooner rather than later.

- Having a range of species can also help provide resilience because if some species don’t do well, then others will grow to fill the gaps.

- Don’t delay planting too long as the top of the silt will dry out. Drilling, if possible, would be preferable to broadcasting and rolling or raking the seed in.

- Silt that is smelly is likely to be anaerobic (or have toxins present) so cultivating it to introduce oxygen is likely to be required. Seeds sown into smelly silt may die due to toxins.

- If using machinery, the silt will need to be dried out enough to be tractable. It is likely the silt will be variable, from more clayey areas where the flood water was moving the slowest, to sandy areas where it was moving fast. Tractability will thus vary as the texture (makeup) of the silt varies, – be careful or you will bog the tractor!

Once you have some plants establishing, getting a full soil nutrient (macro and micro nutrients) and pH test will be valuable, and vital for commercial operations. This is because the silt is likely to have limited amounts of plant-available nutrients, as these are tied up with soil’s organic matter – which is very limited in freshly deposited silt. Adding organic matter will supply nutrients, or use certified organic fertilisers.

Good luck and ngā manaakitanga.

Dr Charles Merfield is an agroecologist and head of the Future Farming Centre, which is part of the BHU Organics Trust. This article used information from a number of sources, particularly resources compiled by www.landwise.org.nz and www.hortnz.co.nz, but have not been personally tested by Dr Merfield.