Join the No-Mow movement!

Dr John Flux’s neighbour once called to see if he had died – because the grass had grown so long! The Lower Hutt ecologist is an advocate of the no-mow movement because of its many environmental benefits, and describes here how he has implemented it for the past four years in his garden and on the footpath verge.

We hope you enjoy this free article from OrganicNZ. Join us to access more, exclusive member-only content

The origin of lawns

Lawns are said to derive from Marie-Antoinette’s wish to show she was rich. The habit spread to English nobility, and then everyone else. Naturalists, the early ecologists, realised how lifeless they were: W H Hudson wrote in 1919: “I am not a lover of lawns… Rather would I see daisies in their thousands, ground ivy, hawkweed, and even the hated plantain with tall stems, and dandelions… than lawn grass.”

The benefits of No-Mow

Today ecologists list many advantages of No-Mow:

- an improved habitat for insects, and the birds reptiles, fish, and frogs that rely on them;

- less petrol for mowing (5% of our carbon footprint);

- increased carbon sequestration, continuing for many years;

- reduced flooding (Cyclone Gabrielle damage was due to cut grass mud-flow, and forest trash);

- it stays green and lowers the risk of wind-blown embers spreading fires;

- and it saves money.

So I started to implement No-Mow in 2021 to show these advantages.

Implementing No-Mow

The first step was to ask the city mayor for permission not to mow the grass verge beside the footpath. He said to contact the environment section, who all thought it a good idea; but verges came under transport. Their only condition was clear views for motorists turning the corner, so the height limit was one metre. Check your local council rules if you want to put No-Mow in practice on your verge or berm.

The second step should be easy: just sit back and watch what happens. But Western humans are born to interfere with nature to make things ‘better’. Resist the temptation, or at least try a No-Mow patch. (Do not expect stability – in New Zealand ecological succession ends in forest, and you may prefer tussock.) I confine gardening to watering, weeding, and fertilising raised beds with compost; no sprays of any kind. We know ragwort is a dreadful weed that will spread everywhere, but it didn’t, as explained later, and monarch butterflies love the two or three plants that flower each year (as pictured in the photo at the top of this article).

Unexpected benefit: two apple crops a year

When we bought this house in 2016 it was in clear view from the gate, but today only the front door is visible. The neat brown lawn now reaches your knees and stays green. I was very surprised at the rate native trees grew once No-Mow established a complete ground cover that prevented the soil drying. They reached four to five metres in five years.

Apple trees (Sturmer, Cox’s Orange, and Russet) are pruned to two metres high, and all three produce two crops a year, summer and late autumn. Other gardeners have not reported this, so it does not seem to be a result of climate change, but pears, plums, figs, and feijoas still bear one crop a year.

Dr John Flux with a Sturmer apple tree in his No-Mow garden. The apples are ripe now (April 2025), and the second crop will be the normal time in August.

Managing the No-Mow garden

This front garden remains No Mow apart from clearing grass against the house for ventilation, and 30cm wide tracks I cut regularly with a push mower for access to prune, pick fruit, and show visitors round. These tracks are now a mix of short grass and white clover.

Most lawns are mixtures of about five grasses, e.g. brown top, fescues (chewings and creeping red), sweet vernal and turf ryegrass is a common lawn. Other species are chosen for a hard-wearing surface (playing fields) or different climates (kikuyu is frost tender). Our berm had kikuyu accidentally introduced in a load of topsoil by the original owner; it dominates that bit of No-Mow (see photo above) and is good for attracting attention – such as when a neighbour called to ask if I had died.

An experiment

On part of my lawn I set up an experiment: half was mowed, weeded, and watered, as normal. The other half has not been touched in any way since 2021 (see below). Each year the No-Mow area grasses grow about 20cm high and flower heads reach 30–50cm. Sparrows and finches enjoy the seeds until it all dies back to the green base over winter.

For the photos below, I cut the flap of grass that normally covers the orange bricks to show the thick underlay, which is ideal for delaying and filtering runoff in heavy rain. Visitors are impressed that no weeds have managed to invade this patch, despite all the dandelions growing and seeding on the mown lawn opposite. It explains why ragwort in the front garden remains an isolated clump. And I hand out copies of God, St Francis, and Lawns (google it!).

Still, problems remain. Ivy spread over a quarter acre of our previous garden, so I pick out every bit I find here. Kikuyu crawls in from the berm, under the fence and under the No-Mow plants. It is very hard to kill; I chuck it back over the fence where it came from. Muehlenbeckia australis climbs everywhere, but can be traced back and cut lower down. M. complexa is the worst, spreading at ground level in all directions looking for any plant to climb in a twisting spiral. I hope copper butterflies arrive soon to eat it, although many insects probe the tiny flowers.

The far side (upper part of both images) shows an identical lawn, completely untouched since 2021, and nothing has changed. Some people expect No-Mow to become wild, but after the first year nothing changes. The lawn flowers and dies back to the same level.

Bountiful biodiversity

Looking across the garden from the front gate to the steps into the house gives a typical view of half the garden. The photo below shows, from left: pale green whau (Entelea arborescens), Muehlenbeckia australis climbing on a dead tree, M. complexa, Castlepoint daisy Brachyglottis spp, pate (Schefflera digitata), Cox’s Orange apple, māpou (Myrsine australis) growing easily through cocksfoot grass with flowers two metres tall, pear, and the tall bare trunk of mountain papaya (Vasconcellea pubescens).

The grass below the trees is being shaded out, and a closed canopy will lead to a totally different ground cover. What will happen?

Ecology education

I try to get people interested in ecology – which has been taught in every school in Russia since 2001, and in China. It explains why cutting berms is now illegal throughout Scotland, and many cities in England do not allow lawns anywhere, only shrubs and meadow flowers.

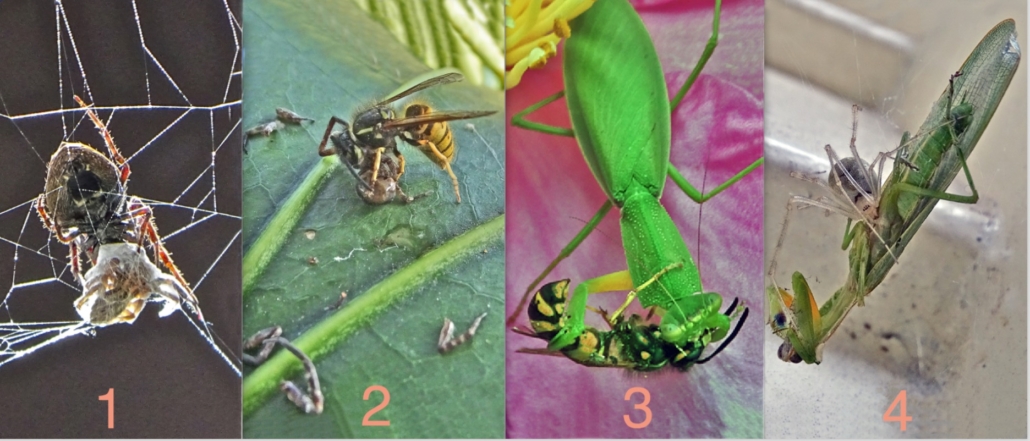

China’s leader in ecological urbanism, Kongjian Yu, completed 200 ‘sponge cities’ by allowing rivers room to spread; stop-banks only make the next flood worse. Two simple rules from Barry Commoner that I find useful are: Everything is connected; and Nature knows best (The Closing Circle, 1971). To illustrate this, below is a predator circle in my garden.

ABOVE: Predators, like weeds, are never simply good or bad: even introduced wasps – they stop cabbage white caterpillars eating brassicas. Pictured from left to right are: 1) spider eating spider, 2) wasp eating spider, 3) praying mantis eating wasp. 4) spider eating praying mantis.