Passionfruit: Small fruit, big benefits

Wrinkled on the outside, vibrant and jewel-like inside, passionfruit is one of New Zealand’s most distinctive summer fruits.

Beyond its distinctive aroma and tangy sweetness, passionfruit offers impressive nutritional benefits, supporting digestion, immunity, heart health and even mood. Small but mighty, this fruit earns its place as more than just a decorative topping, as Paula Sharp elaborates.

We hope you enjoy this free article from Organic NZ. Join us to access more, exclusive member-only content

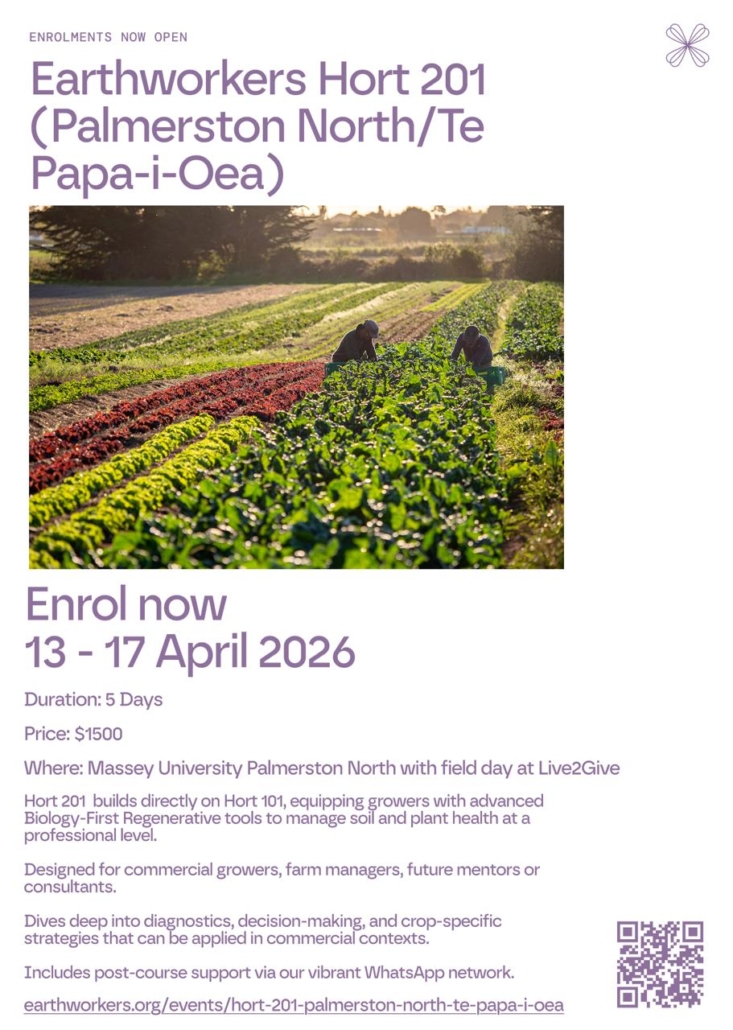

Growing passionfruit

Grown widely across warmer regions, particularly in home gardens and organic orchards, passionfruit thrives with minimal intervention when conditions are right, making it a natural fit for organic growing systems. You can grow it from seed, generally from October to May.

Passionfruit (Passiflora edulis) likes moist, fertile soil and a warm, sunny and sheltered spot.

A framework, such as wires or trellis, is essential for the vine to to climb up. It can be grown alongside a fence, with wires, or even in a tub, with bamboo stakes or tub trellis.

Photo: Eka P. Amdela / Unsplash

A nutrient-dense favourite

Passionfruit is rich in vitamins, minerals and plant compounds that support whole-body health. Just one fruit contains a meaningful amount of vitamin C, essential for immune function, skin health and collagen production. Vitamin A and carotenoids contribute to eye health and cellular repair, while potassium supports healthy blood pressure and heart rhythm.

Focus on fibre

What truly sets passionfruit apart is its fibre content. The edible seeds and pulp provide both soluble and insoluble fibre, supporting digestive health, bowel regularity and beneficial gut bacteria. For those focusing on blood sugar balance, fibre helps slow the absorption of natural sugars, making passionfruit a smart addition to meals rather than a spike-and-crash snack.

Gut health and digestion

Traditionally passionfruit is used in herbal medicine systems for its calming properties, but modern nutrition also highlights its role in digestive wellbeing. The fibre feeds beneficial gut microbes and supports healthy gut motility, the coordinated muscular contractions that move food efficiently through the digestive tract.

The polyphenols in passionfruit act as antioxidants, helping to reduce inflammation in the digestive tract. In organic systems, where soil health is prioritised, fruits like passionfruit often show higher polyphenol content. Healthy soils produce resilient plants, and that resilience is reflected in their nutritional profile.

Photo: Bluesnap / Pixabay

Heart and metabolic support

Passionfruit contains potassium, magnesium and plant sterols that collectively support cardiovascular health. Fibre plays a role in lowering LDL cholesterol, while antioxidants help protect blood vessels from oxidative stress.

For those managing insulin resistance or aiming for metabolic balance, passionfruit works best paired with protein or healthy fats, for example alongside yoghurt, nuts or seeds to further stabilise blood sugar levels.

A gentle mood booster

Interestingly, compounds found in the passionflower family have been studied for their calming effects on the nervous system. While the fruit itself is milder than medicinal extracts, its magnesium content and antioxidant profile can support stress resilience as part of a balanced diet. The sensory experience alone, that tropical aroma and burst of flavour, often brings a moment of joy, which is no small thing in today’s busy world.

Choosing and using passionfruit

Ripe passionfruit should feel heavy for their size with wrinkled skin – smooth skins usually indicate under ripeness. Organically grown fruit may show more surface imperfections, but inside, the pulp remains vibrant and nutrient-rich.

Passionfruit requires little preparation: simply halve, scoop and eat. The seeds are entirely edible and contribute much of the fibre and beneficial fats.

Photo: Bluesnap / Pixabay

Simple Passionfruit Recipes

Passionfruit Coconut Chia Pudding

Serves 2

Ingredients

- 2 tbsp chia seeds

- 1 cup organic coconut milk or unsweetened almond milk

- pulp of 2 ripe passionfruit

- ½ tsp vanilla extract

- optional: drizzle of raw honey or maple syrup

Method

Mix all ingredients in a bowl or jar.

Stir well, cover and refrigerate for at least 2 hours or overnight.

Serve topped with fresh berries or toasted coconut.

Photo: Monika Borys, Unsplash

Passionfruit Yoghurt Dressing

Perfect for both fruit salads or leafy greens

Ingredients

- pulp of 1–2 passionfruit

- ½ cup unsweetened Greek or coconut yoghurt

- 1 tsp olive oil

- pinch of sea salt

Method

- Whisk all ingredients until smooth.

- Use immediately or store in the fridge for up to two days.

Passionflower Tea

The fruit offers vibrant nutrition, but also the leaves and flowers of the passion vine, particularly species such as Passiflora incarnata. This is traditionally drunk as a herbal tea (or herbal tincture) because of its renowned calming properties.

Passionflower tea is useful when you are feeling: mild anxiety and nervous tension, restless sleep, and/or stress-related digestive discomfort.

The plant contains flavonoids and alkaloids thought to gently influence GABA receptors in the brain. These promote relaxation without heavy sedation. It’s often used as part of a bedtime routine or during heightened stress.

NB. While considered safe, it’s not recommended during pregnancy, and anyone on sedative medication should seek professional guidance before use.

How to make passionflower tea

- Place 1 teaspoon dried organic passionflower (leaf and flower) in a teapot or infuser. Pour over a cup of ‘near to’ boiling water.

- Cover and steep for 5–10 minutes. (The longer it’s left, the stronger the flavour and herbal properties. As a sleep aid, steep for 10 minutes or more).

- Strain and enjoy warm.

Ideally, for sleep support, drink 30–60 minutes before bed. For daytime calm, enjoy mid-afternoon.

Photo: CollectingPixels / Pixabay

Want more seasonal nutrition inspiration?

I’m Paula Sharp, nutritional therapist and founder of Paula Sharp Nutrition, supporting women to nourish their health with sustainable food and mindset habits.

If you’d like seasonal recipes, practical nutrition tips and evidence-based wellness insights delivered straight to your inbox, I’d love you to join my newsletter. Sign up at: www.paulasharpnutrition.com

Photo at top of article: Michael Kucharski / Unsplash