Two Manawatū couples with a big vision made hard choices, distilling their operation down to its essence. Rachel Rose talks to the owners of Live2Give about how their business has grown, diversified, adapted, and prioritised, all the while keeping the culture of doing it for good.

We hope you enjoy this free article from OrganicNZ. Join us to access more, exclusive members-only content.

For more than five years, Wholegrain Organics had a commercial kitchen, bread bakery, café, and retail outlet on The Square in Palmerston North, and its team ran food technology and hospitality classes at local schools, under the Hands-On Food banner.

It was underpinned by a big philanthropic vision of serving people and planet, but the operation had become a complex, sprawling operation. By mid-2022, it was fragmented and financially unsustainable – some hard choices were required of founders Naomi and Rob Hall.

“We had a tree with 10 branches, but it was not financially viable,” explains Naomi. “We pruned off eight of the branches and left the two that we saw as foundational, where we can make the greatest difference. The farm is our number one priority – it’s pioneering work, a research farm that shares what we learn. The online shop is the connecting link between the farm and the rest of the world.”

A year on, Live2Give Organics grows vegetables on leased farmland in Aokautere, just south of Palmerston North. Their innovative farming methods produce organic food bursting with nutrients while also improving soil. They are creating healthy, diverse ecosystems on former lifeless paddocks and documenting practices so other growers can benefit.

The relaunched online shop has steadily grown to 160 orders per week, a mixture of subscriptions and one-off orders. It sells certified organic fresh fruit and vegetables grown on the farm (and from other organic suppliers), and a wide range of dry goods from wholesalers.

Lessons hard-earned at Wholegrain Organics have informed the shape and structure of the new enterprises. “Wages are a huge thing, but so are fixed overheads,” notes Naomi. “So now we work from home, out of our garage. It’s tight but we make it work, we’ve reorganised the space four or five times! We also have two chillers, 4.8m and 2.4m long, sitting in the driveway. This way we are not duplicating overheads like rent, phone, internet, and electricity.”

The online shop shares the name and a public face with the farm but is a separate company, run by Naomi and Gosia Wiatr. Rob and Tobi Euerl (husband and fiancé respectively) are responsible for the farming operation, which is a not-for-profit enterprise [see bottom section] but each team helps the other out during peak demand, whether that’s urgent orders to pack or long rows of onions that need weeding.

Supporting other organic growers

Naomi and Gosia are forging relationships with other organic growers to offer diversity to their customers and support to new, small-scale growers. One of these is Crooked Vege Ōtaki, a social enterprise that operates a CSA (community-supported agriculture) intent on regenerative food production that is accessible to all.

“Crooked Vege is an absolutely beautiful start up. Sometimes they have excess produce and we can take that because we sell bigger volumes,” says Naomi. “This week

it was 70 bunches of pak choi and a crate of zucchini. I basically say yes to whatever they have. It was an $800 sale this week, that’s a big boost for them.”

The challenge for small growers is always freight, Naomi explains. Growers can’t access chilled delivery unless they have an entire pallet of produce to move. But Live2Give runs its own chilled delivery truck from Palmerston North to Wellington every week and can backload Crooked Vege’s produce to its hub. It’s a win-win-win situation for both businesses and their customers.

Selling seconds is another considered strategy that helps growers as well as households. “Last year we had crooked cucumbers and cauliflowers that were slug-damaged. We discussed it and decided to let the customer decide,” says Naomi. “We take very realistic photos so people know what they would be getting. We find lots of people don’t mind if organic [produce] doesn’t look perfect.”

They’ve found offering seconds doesn’t harm their sales of first-quality produce. “We still move the ‘firsts’. Also, what we’ve found is people will buy two or three seconds instead of one that’s top quality.”

Selling cheaper seconds is hugely beneficial for budget-conscious customers and great for growers who don’t have a market for imperfect produce. An organic avocado grower in Tauranga, for instance, could only irregularly supply export-quality fruit, but has loads of very slightly imperfect avos. Live2Give customers are loving them.

Live2Give prefers to source from certified organic growers, but make exceptions for small-scale growers they personally know are using organic methods.

While customers are welcome to just buy what they want as they need it, or customise their box subscriptions on a week-to-week basis, it is the regular orders that are incredibly valuable to an organic grower.

“You do feel vulnerable because you’re waiting to hear the dings on the phone as the orders come in,” reflects Naomi. “There’s absolutely no guarantee that people will order anything. It’s really heartwarming how order numbers have steadily increased this year.”

Growing the business

Gosia and Naomi knew they’d miss the personal interaction they had with customers and students through Wholegrain Organics so thought hard about how to stay connected. Gosia launched a weekly email before they had produce to sell and now their mailing list is over 5000 people. They use Shopify for ecommerce and their email campaigns. Gosia gathers a lot of insight based on what people read, what they click on, and what they buy.

She observes that some people may subscribe to the email for months before they start to order and thinks that an online retailer needs to win people’s trust and that may take time. The newsletter, website, and social media feeds are important ways to educate people about the benefits of regenerative farming, to show the passion and labour involved, and to illustrate the costs behind organic production.

Social media is a clear winner when it comes to growing their customer base with 80-90 percent of new customers acquired from advertising on Facebook and Instagram. Gosia says it is useful to be able to target very specific audiences. Their advertising highlights the freshness of their food, the way it is grown, and the benefits to the environment and those who eat it.

Everyone involved puts a lot of effort into providing the freshest possible produce: harvesting at the ideal time, immediately chilling vegetables to remove field heat, and using sturdy reusable crates to keep produce cool and undamaged in transit.

The vertical interaction of their operations starts on the farm and finishes with handing produce personally to their customers. Gosia has been at the wheel of their chilled truck all last year, dropping off boxes to customers right down to Wellington every week. They’re looking to hire a driver but want to find the right person to be the face-to-face link with customers. “It’s important to have someone who has worked on the farm, in the shop, and shares the same values around connecting with the community, working with nature, and having a healthy lifestyle,” says Gosia.

Community connections

Live2Give hosts an open day once a year at the farm sites, one for customers and another for farmers interested in knowing more about the innovative regenerative agriculture techniques they are using.

Happily, the new business model hasn’t seen an end to interactions with youth. “We’re so close to Massey and IPU [universities]. We have students that seek us out; it’s great to work with young people who are interested in what we do,” says Naomi. And Gosia thinks being hands on, at the farm or in the packing room, is a more powerful learning experience than simply reading about regenerative agriculture. As well as part-time staff, there are a couple of older volunteers who like to help out because of a shared commitment to Live2Give’s goals.

“What I love about this business is we’re holding hands with our customers to get to the same goal,” says Naomi. “Us, the growers, our customers, all together we’re making it work.”

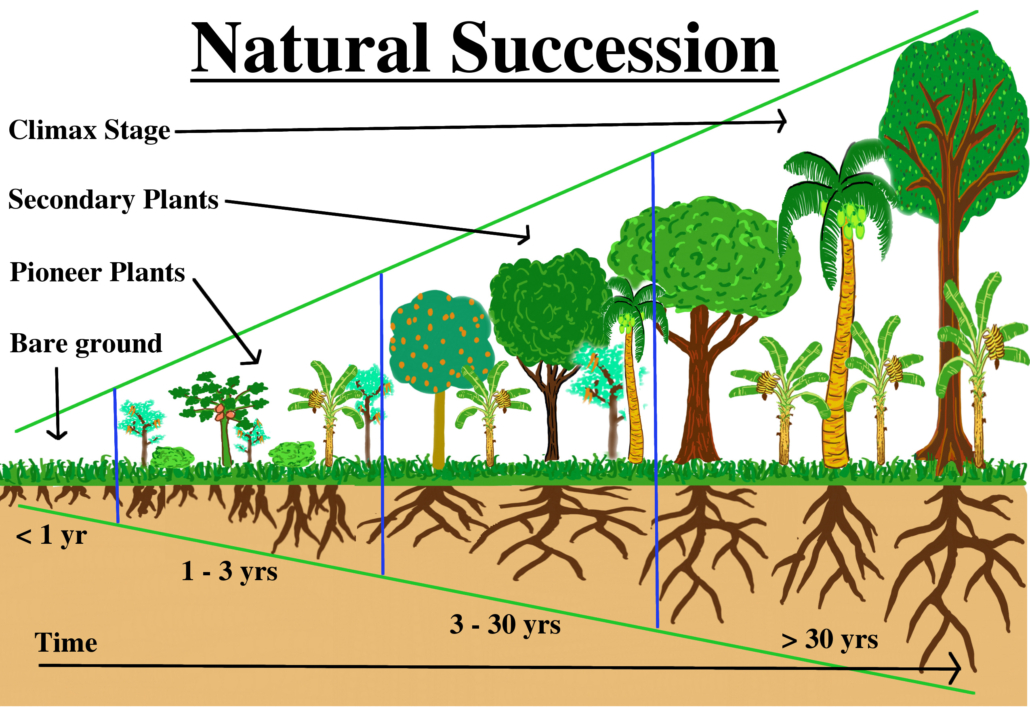

Live2Give are pioneering farm-scale regenerative horticulture in Aotearoa, building on 12 years of research and development in Germany by a farm of the same name. “Always cover, always roots” is their mantra: the soil is protected and improved by growing carbon crops in between cash crops. The roots are left to decay in the ground, improving structure and feeding the soil microbiome.

Rob and Tobi grow crops on three parcels of leased land, of which approximately four hectares is in full production. The sites have no history of chemical use and are certified with OrganicFarmNZ. In addition to the mulch, crops are fed with granulated fertiliser. Seaweed sprays, bought-in compost, and EM (effective microorganisms) sprays are currently being trialed.

Only the greenhouse crops are irrigated. It’s not a high rainfall area, about 900mm/pa. Drought years are a concern but dumping rain is just as much of a problem. The main site has a gley (sticky clay) soil, wet in winter and spring.

Detailed crop planning balances a strict seven-year crop rotation while also ensuring the farm can supply produce for 12 months of the year. Their record-keeping is exemplary and the numbers feed into farm planning and fine-tuning their methods.

About a quarter of the farm’s produce is currently sold through the Live2Give online store; the rest is sold to organic retail outlets in the major cities. Having multiple outlets creates flexibility and ensures they won’t be left with more produce than a single market can sell.

Some 70 percent of the vegetable offerings in the Live2Give shop are from its own land. It could be more says Rob, but that would limit the time he and Tobi have to devote to research, which they see as fundamental to their purpose. The farm has funding from MPI’s Sustainable Food and Fibre Futures for an almost four-year proof-of-concept trial, of mulch-direct planting for commercial vegetable production in New Zealand conditions.

What’s ahead? “We are unsure of what [growth] to project for the next 12 months but our aim is food security. The Covid lockdowns highlighted that need and extreme weather events are a constant reminder of how difficult the environment can be for food production. We are caring for both the environment and the local community, connecting these things together. This needs healthy growth for ground level food producers, not skyrocketing demand because of a pandemic, or scarcity because of flooding or drought,” reflects Rob.

(Photo Credits: Rachel Rose / Live2Give)

When she returned to New Zealand in 2010, Rachel Rose retrained, studying organic horticulture, biodynamics, and permaculture. She used her knowledge to establish extensive gardens and orchards on a 1400m2 urban plot, and is now applying it to a 28-hectare farm near Whanganui.