Loving soil, but also learning soil

By Jenny Lux

This article was first published by Earthworkers and is republished here with their kind permission.

We hope you enjoy this free article from OrganicNZ. Join us to access more, exclusive member-only content

I have always been a details-oriented sort of person. As a child I remember planting flowers with my Mum, learning all of their names and pressing them in a flower press. I later I revelled in learning how to identify and use the three names of all our native vascular flora (Māori, English and scientific). My first career was in plant ecology, after I did a Masters in that area looking at the relationships between soil and the regeneration of kauri forest after fire.

Moving between the details and the big picture, I became seriously concerned about climate change around the time of my late twenties. Not just mildly concerned as I had been in my youth, but in-your-face, losing-sleep, suffering-existential-fear-and-anxiety level of concern.

Of course, this had coincided with finding a husband who was a big-picture thinker and having two wonderful baby boys. I did not end up giving up at that point, but I decided that when I got back to paid work, I would be dedicating my time to a career in climate action.

Growing vegetables

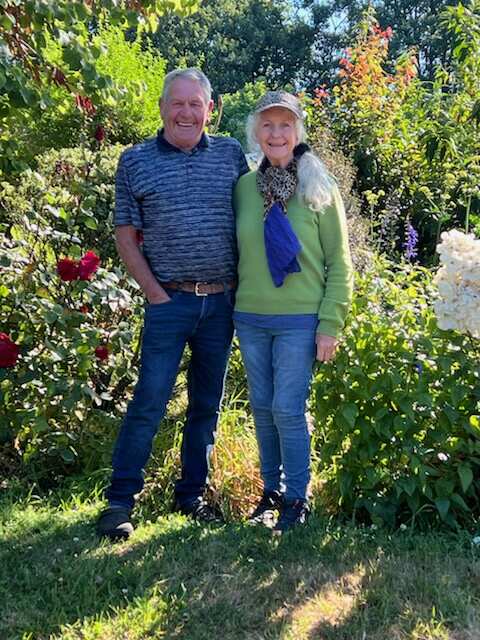

I moved from field-based plant ecology work to growing and selling organic vegetables, as a home-based profession that could keep me close to our kids and our food. Richard helped me establish Lux Organics, a small-scale organic market garden on the outskirts of Rotorua. He initially kept his day job as an ecologist, but then joined me full-time in the business for three years. My parents got involved, providing a generational backbone to the business.

We grew beautiful vegetables for our community, and by the time the Covid crisis and lockdowns occurred, we were able to pivot to vege boxes, bringing them to peoples’ doors with our electric van. We started hiring seasonal staff in 2020, which meant a succession of people learning the organic growing methods with us. By 2023 we had added solar panels to our shed, powering our household, vegetable chiller and van with the sun.

This has been a journey of creating a business that minimises carbon emissions while growing food. Hand tools, electric tools and hands in the soil have been our main inputs. The productivity of our soil has been the foundation of our business (as it is for all farming) and we have strived to care for it, taking soil tests each year, and learning about every aspect of soil health along the way.

When you grow a crop for market, and especially when you grow over 40 of them (!), there are a lot of questions and uncertainties about how to manage the soil, what might be affecting the outcomes you’re seeing, how to solve problems, and how to keep producing all through the seasons.

These veins of query are what led me to the five-day Earthworkers Regenerative Horticulture 101 course in the winter of 2021. I attended with two of my staff and I encountered a whole group of amazing people involved in different sorts of projects who were on my wavelength.

I discovered new terms which opened up my mind to the soil ecosystem in a new way. Quorum sensing, cation exchange, paramagnetism, root exudates, polycropping. I have kept in touch with the group ever since (online and in person), and this has led to multiple fertile exchanges and more farm visits, opportunities to learn and even to help others. It’s a magic human interaction!

In recent years, with the domestic recession, business has been tough, as local people cut their organic vegetable spending. Looking at in a big picture way, it’s a manifestation of how people cannot/do not make longer-term environmental and health choices when they are poor and worried about their daily survival. Our business relies only on its connection with the local food system, rather than export.

While we experienced a huge high after the Covid crisis, when people suddenly became concerned about the sustainability of their local food supply, we are now in a phase of relentless cost-cutting. Our customer base has concentrated to only those who value food produced in a way that is free from contamination, and which looks after land.

Now that I have been working in practical agroecology on my own land for over nine years, I am curious about taking my soil knowledge deeper and broader, to have a wider impact. It’s one of those cliches… the more you learn, the more you realise you don’t know, and it becomes impossible to give simple explanations any more.

I would now never say, “ah, just use compost and everything will be fine”. There’s a lot more to growing, and to soil, than most of us really, truly understand. My curiosity burns and I want to know which levers to pull to achieve the healthiest crops and soil. Looking again to the bigger picture, how we manage soil on our productive land is the probably the most important aspect of New Zealand’s climate emissions profile.

This is why I’ve dedicated pretty much all of my market garden earnings in 2025 so far to further study and investing in my own knowledge growth.

I have taken papers at the University of Waikato in soil science and hydrological management, and I have attended specialist courses by regenerative educators (Graeme Sait from Nutri-tech Solutions, and Nicole Masters from Integrity Soils).

I am building up a research library and reaching out to soil mentors for the next step in my career. I even bought a microscope from a fellow Earthworker (thank you Coral).

All of this new learning is feeding directly into the next stage of my journey — growing my skills, confidence, and contribution through the Earthworkers community.

Over the next few months, I’ll be deepening my learning through the new Regenerative Horticulture 201 and Future Agronomists courses, working directly with Daniel Schuurman as we develop and pilot both programmes. My goal is to grow my capacity as a biology-first regenerative agronomist — someone who can read the soil, guide other growers, and support the shift toward biology-led farming across Aotearoa.

In 2024 I mentored for For the Love of Bees on their year-long Communities of Regenerative Learning programme, which opened a new path for me as a mentor within the sector. That experience, and my continued involvement supporting new growers through the post course Earthworkers WhatsApp network, has shown me how powerful it is when we stay connected — helping one another, sharing knowledge, and learning together every day out in the field.

I look forward to doing Regenerative Horticulture 201 in 2026 and keeping up my active learning and practice. Growing in soil is a bit like general life… you can’t follow one set recipe. Things keep moving and changing, and you have to be observant, responsive and kind.

Jenny Lux is a former chair of the Soil & Health Association. Find Lux Organics online here.

Earthworkers has launched

The natural evolution of For the Love of Bees, Earthworkers has a new hub to support biology-first regenerative horticulture in Aotearoa.

After a year of development they have launched a brand new website, and a full learning pathway.

Enrolments are now open for 2026:

- The foundation course Hort 101 (4–8 May, Mangaroa Te Awa Kairangi – Wellington region)

- The advanced course Hort 201 (13–17 April, Palmerston North, in partnership with Live2Give)

Both courses come with post-course support via a WhatsApp chat network to help growers transition to resilient, profitable, biology-first regenerative systems.

Earthworkers’ first alumni blog, Cultivating Knowledge Together, features Jenny Lux— an experienced grower and organic advocate who will be one of the first participants in our new Hort 201 and Future Agronomists programmes, designed to grow New Zealand’s next generation of biology-first agronomists.

Explore the pathway: earthworkers.org

Earthworkers courses in 2026