Shelf life – or human life?

Ultra-processed foods are all about shelf life rather than human life, writes Dee Pignéguy.

We hope you enjoy this free article from OrganicNZ. Join us to access more, exclusive members-only content.

There is a new system of industrial food manufacturing that produces edible substances that are not food, but rather food products containing novel, synthetic molecules never found in nature. These ever-increasing laboratory-engineered chemistry experiments are designed to simulate food.

Any substance that cells and tissues cannot assimilate from the bloodstream to be transformed into materials that the body can utilise is not a nutrient. If it cannot be metabolised it is a poison, or at best a completely unnecessary filler.

The soy industry is one of the main feeders to ultra-processed foods. The logic of ultra-processed food is you take commodity crops, such as corn, rice, soy, wheat, a small number of animals, pigs, cows, and chickens, and you reduce those commodity crops to almost molecular components. Then you get things like soy protein isolate, modified starches, high fructose corn syrup.

Fake food made by robots

Production has become almost entirely automated, with computer-controlled robots cutting vegetables, grinding meat, mixing batter, extruding dough, and wrapping the final product.

Many additives are required so food can withstand the process of this robotic mauling, before the basic molecular constituents are re-assembled into food-like shapes and textures with a nearly infinite shelf life, heavily salted, sweetened, coloured, and flavoured.

Petrochemicals in our food

In the United States, around 10,000 different food additives, and many of the chemicals used to create these additives, are derived from petrochemicals and are inherently toxic. There are humectants, foaming agents, anti-foaming agents, bulking agents, emulsifiers, stabilisers, non-nutritive sweeteners, modified starches, guar gums, xanthan gum, flavour enhancers, acidity regulators, preservatives, antioxidants, carbonating agents, gelling agents, glazing agents, chelating agents, bleaching agents, leavening agents – all of which serve slightly different functions. Emulsifiers are nearly universal in ultra-processed foods.

The method of construction means the ultra-processed foods (UPFs)s are generally soft. Industrially modified plant components and mechanically recovered meats are pulverised, ground, milled and extruded until all the fibrous textures of sinew, tendon, cellulose, and lignin are destroyed and can now be reassembled into any soft, dry shape, almost pre-chewed but calorie dense and easily digested. This dryness stops microbes from growing and decomposing ultra-processed food, which is one of the keys to long shelf-life.

Drivers of disease

What if diseases do not exist? What if they are really expressions of an underlying disruption to the body’s normal function that manifests a variety of different systems?

Trans-national corporations continue to shape food systems on all levels, expanding the UPF industry at the expense of traditional foodways. UPFs are the fastest-growing segment of the global food supply and a major driver of increasing diet-related, non-communicable, and stress-related diseases worldwide. UPFs can cause cellular stress, damage the delicate mucosal linings, cause intestinal inflammation, and reduce immune response to bacteria.

The guts of the issue

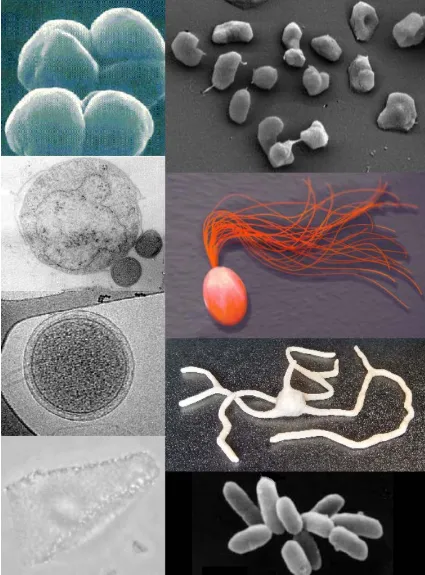

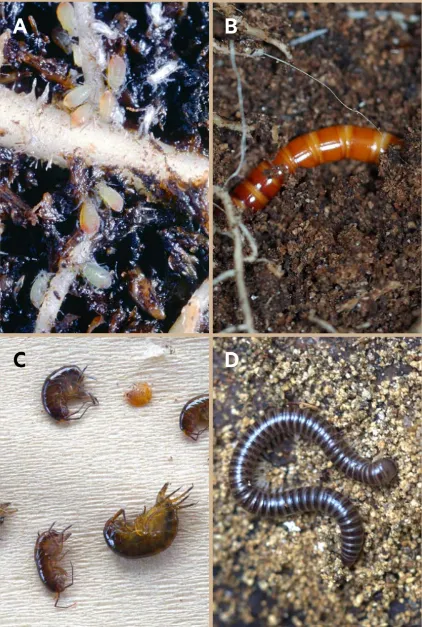

For every one of your cells there are by some estimates 100 other organisms living as part of you. The largest number of organisms is in the gut, at the end of the small intestine (where food is digested) and throughout the large intestine or colon where water is absorbed and fibre is fermented. Human colons have among the highest densities and greatest diversity of bacteria of any environment on earth. These gut microbes form our digestive engine. Caring for this unique community that makes up our body is linked to good health, especially eating a good diet.

When the gut lining is damaged by fake food the microbiome changes which can result in the destruction of the local culture and ecosystem—called dysbiosis.

Healthy and whole

Whole and minimally processed foods, especially organic foods, are associated with a positive ecology of friendly bacteria in our intestines, such as fibre-fermenting lactic acid bacteria.

This healthy ecological system is damaged when ultra-processed food damages the gut lining and changes the microbiome. Healthy bacteria are overtaken by unfriendly bacteria, resulting in low-grade systemic inflammation, which becomes chronic inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract over time, causing the body to produce chemicals that wreak havoc on our organs and arteries.

Who bears the burden?

Excessive and unnecessary inflammation accelerates heart disease. You don’t just wake up one day and have cancer or heart disease; it’s a process not an event. There is a limit to the ability of the human body to function properly under a constant barrage of toxic substances.

We are now living in a world where one in three children by the age of eleven is at risk of diet-related disease. Studies confirm that stress from any source, but especially the chronic stress of poverty, has dramatic impacts on the hormones that regulate appetite, increasing the drive to eat.

Why do activists and civil society groups have to bear the burden of proof to show that adding thousands of entirely synthetic novel molecules to our diet might be harmful? There is no functional regulation of food additives in the USA – or New Zealand – that can ensure food is safe, and the burden of proof is not on the companies to demonstrate long-term safety of the additives that they produce.

UPFs bad for people and planet

Many UPF products contain ingredients from four or five continents – for example palm oil from Asia, cocoa from Africa, soy from South America, wheat from the USA, flavourings from Europe. Many of these ingredients will be shipped more than once—from a farm in South America to a processing plant in Europe, then to a secondary processing and packaging plant in another part of Europe, then to consumers. Imagine if we were using organic farming, we could increase food quality and diversity while reducing the external costs of ill health and climate change.

UPFs harm the environment though production and use of plastic selling billions of products in single-use bottles, sachets, and packets. Creating a world without waste is impossible if companies continue to focus on producing ultra-processed ‘foods’ which drive environmental destruction, carbon emissions and plastic pollution.

Even though young people have a right to grow up in an environment where healthy affordable food is the real option, in New Zealand over two-thirds (69%) of packaged foods were considered ultra-processed, that is ready-to-eat or -drink items based on refined substances, often with added sugar, salt, fat and additives. Before the mid-twentieth century, beyond a few products such as margarine or carbonated soft drinks, ultra-processed foods did not exist.

Motivated by money

Money drives the ever-increasing complexity of each layer of processing which extracts a little extra money from the low-quality, often subsidised crops. Each layer of processing or reformulation increases the range of possible products.

Corporate growth is driven by marketing and advertising, not public health. Supermarkets and corporate shareholders, over which there is little regulation, are dictating what you can buy and driving a new age – commerciogenic malnutrition – malnutrition caused by companies! So, vote with your pocket when shopping – whether at the supermarket, organic shop or farmers’ market.

Healthy cooking habits :

A bit of time, planning, and preparing things in advance can save you time and money later – and improve your health.

- Make your own pizzas – everyone can choose their favourite toppings.

- Homemade muesli rather than sugary breakfast cereals.

- Think ahead and make extras (e.g. muffins, meatballs, sausages etc.) to pack in lunchboxes.

- Homemade bread – let it rise overnight and bake in the morning.

- Make your own tomato sauce or plum sauce (you control the sugar!)

- Pick one day a week to cook up a big batch of something your family likes, and freeze in batches for later use.

- To save money, buy in bulk e.g. fill your own containers, or join a food co-op.

- Be creative with leftovers!

- Grow sprouts on your windowsill to use in sandwiches, salads and as a garnish.

- Take kids into the garden to identify and pick salad greens.

Healthy snack suggestions:

- Fresh fruit

- Carrot sticks, broccoli stalk sticks and hummus

- Boiled eggs

- Cheese and crackers

- Nuts and seeds

- Toasted pumpkin and sunflower seeds with a dash of soy sauce

- Dried fruit (fresh fruit is better for your teeth)

- Homemade scroggin mix

- Nori seaweed sheets

- Miso soup in a cup

- Muffins made with carrot, pumpkin, apple etc

- Wholemeal bread sandwiches.

In all her education work Dee Pignéguy weaves together the skill of gardening with the critical link of food and nutrition. Most of today’s chronic diseases are associated with inadequate nutrition.

Her nutrition book Grow Me Well – available via papawai.co.nz – will help you make the leap to healthy eating.